The pages of Bengal’s centuries-old history are filled with ‘cries of despair’ and macabre events, posing challenges for generations of historians, sociologists and chroniclers. When tillers of the land, forest dwellers and hunters rose up to fight for their lives, and ways of life, it was a series of upsurges, rebellions and revolts.

Expressed in different ways, it became a part of people’s memory often referred to as folk stories or myths shrouded in the mists of time. What began in the 1770s has continued till date; geography remains the same ~ the forests and fields of Bengal, today’s Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and adjoining Bihar and Odisha. An early spark was provided by East India Company armies in the forest-rich areas and fertile lands of Midnapore, Birbhum, Bankura, Rangpur, Dinajpur, Ranchi, Hazaribagh, Manbhum and Santhal Parganas.

Once they began exercising their right to extract maximum revenue from the land and forests, often ruthlessly and remorselessly, violence erupted. Issues of land rights and farmers’ entitlements, forest produce and revenues being paid to the foreign, local authorities came to the fore.

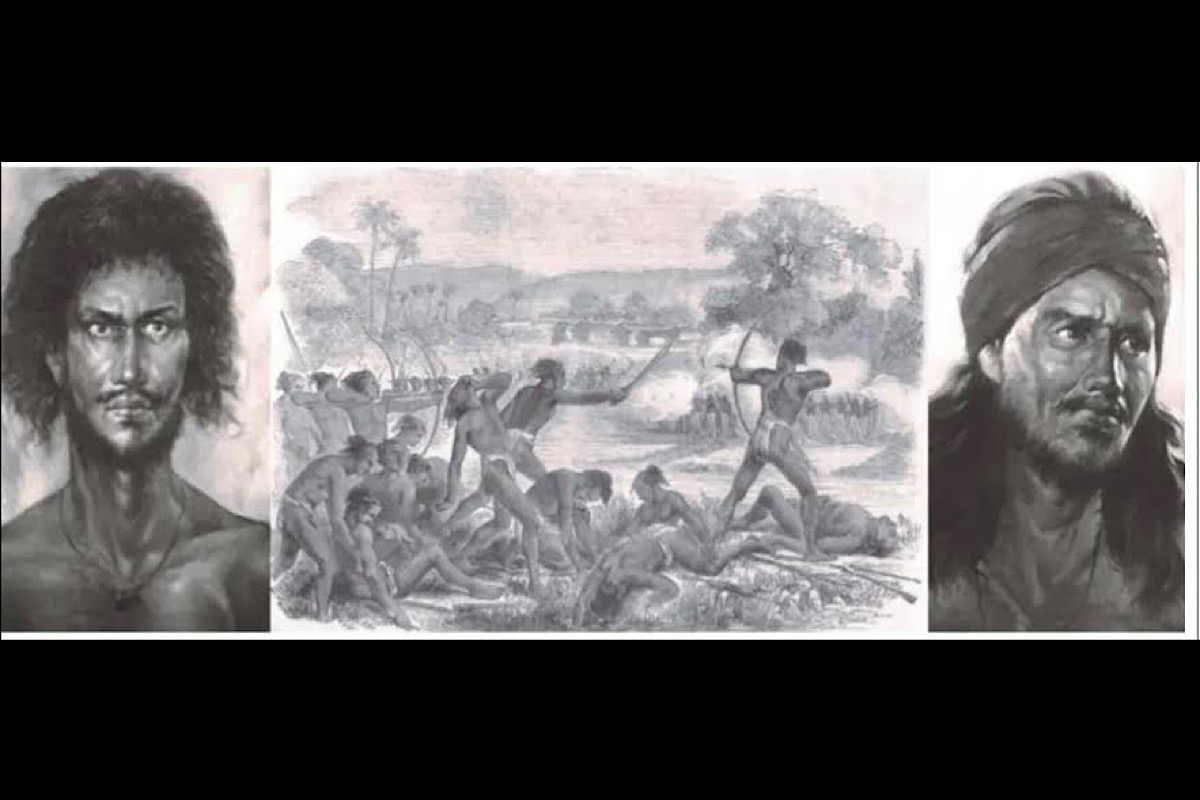

This fire spread across today’s states of Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Odisha, and the names of its fiery rebel-leaders became part of anti-colonial history which began in the 18th century: Tilka Manjhi, Bhawani Pathak, Debi Chowdhurani, Majnu Shah, Cherag Shah, Sibchandra Nandi, Dirji Narayan, Kena Sarkar, Nuruluddin, Israel Khan, Achal Sinha, Durjan Singh, Bakshi Jagabandhu, Tipu Garo, Shariatullah and Dudu Mian, Sidho and Kanu Murmu. It is the roster of grassroot rebel-leaders, with strange-sounding names, who challenged the might of the East India Company and local zamindars.

They sought and fought for equality, justice, and peace in their land. No wonder they remain ‘alive’ for the universal values they espoused; rebel-heroes unafraid to sacrifice their lives for bigger causes. The clarion call of leaders, often in songs, was powerful as heard during the Rangpur rebellion in 1783. The folk song of Ratiram Das: “Listen o peasants/ You are the King’s wealth, his real treasure/ Go to Rangpur in your thousands.

Attack, destroy, loot Debi Sinha’s home”. Thousands not only reached Rangpur and besieged the Ijaradar Debi Sinha’s haveli, the rebellion spread to neighbouring Dinajpur. It was the Company’s forces which crushed this rebellion by executing hundreds of tribals and peasants.

A major feature of this rebellion was the unity demonstrated by Hindus and Mussalmans, according to ‘India’s Struggle for Freedom ~ An Album’, a Government of West Bengal publication. Termed by historians as the Sannyasi-Fakir rebellions, it raged for four decades, from the 1760s to 1800s. Men, who had abandoned their homes for spiritual quests, were joined by artisans and demobilised soldiers who organized sporadic revolts against the British Raj.

Across Bihar, north Bengal and upto Dacca and Mymensingh, names of Bhawani Pathak, Debi Chowdhurani, Majnu Shah, Cherag Shah were revered by the landless poor and dreaded by the British engaged in enforcing their administration. At the end of the 18th century CE, when the East India Company got its exploitative commercial-administrative act together, and Lord Cornwallis gave to the subcontinent the Permanent Settlement of 1793, there was another wave of revolts, rebellions, and armed attacks against the British.

In Midnapore, Bankura and Jangal Mahal, from 1798 till 1816, the series of uprisings are termed as ‘Chuar’ and ‘Laik’ rebellions. Chuar is a derogatory term, referring to pigs or petty robbers; obviously lowly tribals and landless poor were abused, kicked around by beneficiaries of the new land settlement.

These included zamindars, talukdars and landlords, who in perpetuity, had agreed to give fixed rent to the Government. Thus was created a loyal landed class in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa who strengthened British rule and rode roughshod over the lowly Chuars. The collector of Midnapore in a letter to the Board of Revenue wrote, “Those who were enjoying the right to this land since the antiquities, when they saw that their land being taken away from them without any rhyme or reason, or that an excessive amount of revenue was sought to be extracted from them, then they took to arms in defence of their rights.” Durjan Singh, often hailed as a Raja among the Munda tribals, assumed leadership and with 1,500 men established their rule in Raipur Pargana. In their fearlessness and scant regard for their lives, they attacked seats of government power, in some places, zamindari records were burnt and army barracks destroyed.

Unable to sustain the rebellion, Durjan Singh and his men were mowed down by the Company forces. Close to the Chuars were the Laiks, living in Bogir near Garbeta in forest areas. Their leader Achal Sinha demonstrated his fury against the Raj. Adopting guerilla tactics, they repeatedly attacked British camps, leaving the foreigners no option but to destroy the entire forest by heavy artillery fire around 1815.

Achal Sinha was trapped, with the aid of a treacherous aide, and promptly shot dead. Some 200 rebels were brutally executed. WW Hunter’s Annals of Rural Bengal, published in 1868, provides an often-overlooked context to understanding these rebels and rebellions: the famine of 1770 and its horrific effects on the lives of ordinary people. Hunter noted, “All through the stifling summer of 1770 the people went on dying.

The husbandmen sold their cattle; they sold their implements of agriculture; they devoured their seed-grain; they sold their sons and daughters, till at length no buyer of children could be found; they eat the leaves of trees and the grass of the field, and in June 1770 the Resident at the Durbar affirmed that the living were feeding on the dead.” In the Annals, we meet young John Shore, who landed in Calcutta in 1769 to work as a writer in East India Company.

His poetry is referred to as an eyewitness account: “Still fresh in memory’s eye the scene I view / The shrivelled limbs, sunk eyes and lifeless hue/ Still hear the mother’s shrieks and infant’s moans / Cries of despair and agonizing moans…/ Dire scenes of horror, which no pen can trace / Nor rolling years from memory’s page efface.” Shore became the Governor General of Bengal in 1793, leaving this highest office in 1798. Hunter refers to reports of Warren Hastings, who noted “the loss as at least one-third of the inhabitants. It represents an aggregate of individual suffering which no European nation has been called upon to contemplate within historic times.

The famine had within nine months swept away ten million of human beings”. Later when recording the Kol uprising of 1831-32, John Shore said, “nearly 5000 sq. mile territory had to be devastated by the British, in order to crush the uprising”. Kol, Munda and Ho tribals showed remarkable courage and daring, facing the army with only hatchets in hand.

It was in June 1855 that the leadership of Sidho and Kanu Murmu emerged with the uprising in Santhal Parganas. In a massive rally of over 10,000 Santhals in village Bhagnadihi, they took an oath to end oppressive rule of Britishers, zamindars, moneylenders and to set up an independent Santhal raj. A large army comprising tribal warriors, blacksmiths, artisan-potters, cobblers, and weavers marched towards Calcutta.

Oppressive moneylenders and police officials were killed by them. In July, they killed a notorious police officer, declaring the aim of their rebellion to overthrow the rule of East lndia Company. There were pitched battles with Company forces who were defeated. Santhal rebels besieged the fortress at Pakur, where retreating English had taken shelter. Sidho and Kanu captured Pakur fort, then marched towards Murshidabad.

Half of the district of Birbhum saw a veritable collapse of British rule, at the peak point of the rebellion. From Birbhum to Bhagalpur, British power was totally disrupted. In November 1855, martial law was declared and the Army moved in. WW Hunter recorded in the Annals, “what we fought was not a war. The Santal did not know the meaning of surrender. So long as their drum went on beating, they went on fighting to the last man.

There was not a single sepoy in the British army, who did not feel ashamed for this courage.” Except for the revolt, mutiny, and war of independence of 1857-58, so many people were never killed in any other mass revolt.

It is said 30 to 50,000 Santhals were fighting for their rights; the British killed 15 to 25,000 rebels, according to ‘India’s Struggle for Freedom ~ An Album’. Bhagnadihi, where the fire of revolt was light is today’s Bhognadih village, Barhait block in Sahibganj subdivision of Jharkhand.

Visits by dignitaries to garland statues and memorials continue till this day; Sido Kanhu Murmu University in Dumka, Jharkhand is a tribute to the two Santhal ‘freedom fighters’ who led the Santhal Hul, as the rebellion is popularly known. When in July 2022, Smt. Droupadi Murmu was sworn in as the 15th President of India, she became the first Santhali tribal leader to grace the highest public office in India.

(The writer is a researcherwriter on history, heritage issues, and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)